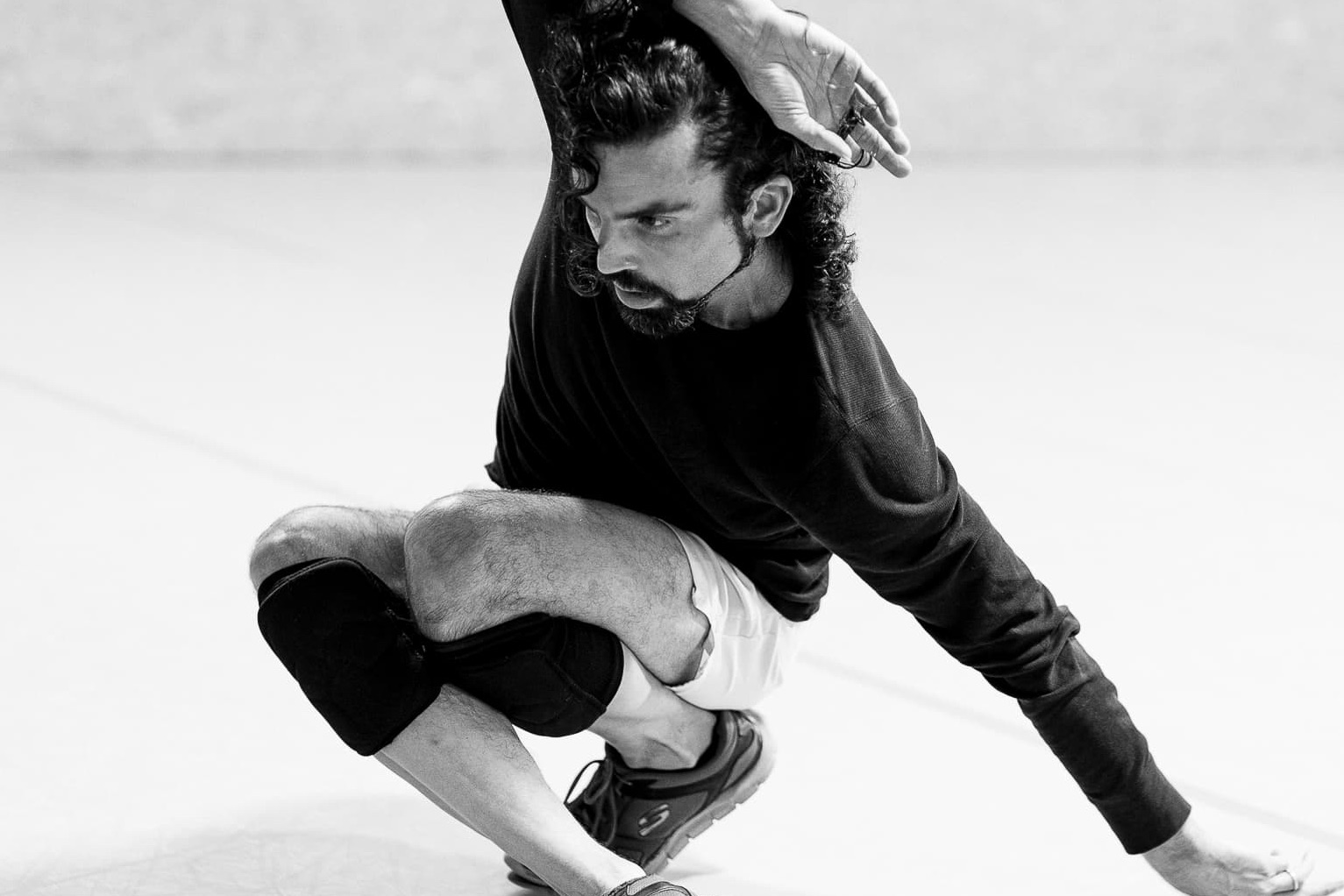

Ahead of the TOIVOLA festival in Helsinki, Brussels-based choreographer, performer, and researcher Kevin Fay shares insights into his upcoming performance blood and thunder and its workshop conversing with masculinities. In conversation with the Institute’s programme assistant Tilda Forss, Fay discusses his collaboration with French sound designer Guillaume Soula, how performance can be both deeply personal and politically resonant, and the balance between structure and improvisation in his artistic process.

« I’m speaking from the heart in this festival – proposing intimate forms of contact around themes that are important to me. »

Tilda: At the TOIVOLA festival you’ll be both performing and hosting a workshop, centred around masculinity, feminism, language, and the body. What would you say to prepare the audience for these experiences?

Kevin: For blood and thunder, Guillaume and I are excited to create something that feels immersive, current, and shared. Personally, I imagine the performance as a conversation. I always want to feel close to the audience, because the themes you mention feel close to me, and intimacy is an important motor in my work.

For that reason, the theme for this year’s festival – “love” – made me think about what love requires and allows. The word “trans” felt important to me because I situate myself as an artist-activist. While I’m not a trans person, I want to support the trans community at this moment, more than ever. What’s more, the theme love introduces the opportunity to think of movement across, beyond, or through. I’m speaking from the heart in this festival – proposing intimate forms of contact around themes that are important to me. At the end though, I want it to be about what we’re dealing with in the world.

For conversing with masculinity, I’m not suggesting that the workshop is a situation where I solve the world’s problems or give you answers to hard questions, but it is a way of pointing at huge themes, and approaching them with artistic tools – through reading critical texts, listening, conversing, dancing in duos, and drawing, for example. Politics is part of my personal work, and as a white, male-identifying person from the United States, I recognise and do not take for granted the responsibility I have when facilitating workshops that deconstruct something that I very tangibly represent. That is, I grew up in Washington, D.C., and I went to an all-boys’ high school that’s three blocks from the Capitol building. So, as someone deconstructing their place within patriarchal culture, I want this to be an accessible experience that offers an opportunity to find a sense of ease through connection – or even a sense of collective power – inside circumstances that can be overwhelming.

Tilda: How do you see your work fitting into the TOIVOLA festival, and a Finnish context?

Kevin: I love Finland, and I feel very lucky and excited to go. Veli Lehtovaara is a long-term artistic collaborator of mine, and he is the person who introduced me to Finland in 2018. In this case, Jani Toivola’s theme of love really drew me in, especially with bell hooks’ book All About Love fresh in my mind (I love hooks’ work, and I really recommend this book to everyone). Also, the fact that the performance is not onstage in a theatre is very exciting to me. Performance environments are sacred to me because they allow an intensification of human experience. As a sensitive person with a desire to combat normative ideas about masculinity and binary gender, I choose to create performances that allow for intimacy because that intensification is not immediately evident, safe or common. Like that, I try to use performance to make a statement and offer a unique experience. I believe that’s why I created a performance that allows for a lot of intimacy. I realise not everyone enjoys proximity – especially in Finland perhaps – so I, of course, remain respectful of boundaries. At the same time, I also think that acknowledging the presence of boundaries and offering a way, with performance, to peer outside of them, is very important. For this reason, the plasticity of bodies and minds is fundamental to the somatic work I practice, and it inspires the work I do with Guillaume to create immersive environments and acoustics that produce something sensuous and malleable.

« Performance environments are sacred to me because they allow an intensification of human experience. »

Tilda: Have you seen the workshop conversations differ from setting to setting?

Kevin: Over the years, I’ve worked with many different age groups and with people of all backgrounds. With partners like arts centre BUDA in Kortrijk I could share workshops with the ‘compañeros’, a group of people who are typically older than me, and during the pandemic, I offered Zoom sessions to students at my former high school in Washington, D.C.. Yet, artistically, I’m fascinated by alchemical processes of finding words for feelings. Examining the space between the body feeling something and the brain comprehending the feeling is different for everyone. So, while it’s not possible for me to generalise across groups, yes, different things have emerged because of people’s different backgrounds. In any case, it’s vulnerable, asking people to reflect in a somatic way, with breathwork practices, or scores for improvisation, inviting them to really be with the history and emotion of their flesh. That’s not something I take for granted during the workshop, but care for very proactively.

Tilda: Intimacy, or as you call it, the motor of the performance, must be hard to predict and play with. How do you encounter improvisation?

Kevin: I love improvisation. I do a lot of it, and I always will. It’s powerful for the freedom and the freshness that it offers, and tender because it’s personal – changing day to day and revealing real thinking and feeling in motion. That said, Guillaume and I started working together last year, and we really want to keep developing the relationship we have. In this, we both start with improvisation, but agree on anchors in order to track the development of each other’s material. For me though, there’s something generative about the multiplicity of the body in motion. I imagine the body doing the ‘talking’, so editing, reducing and focusing, are part of what I work on with Guillaume, but if things become too produced or planned in advance, then intimacy can become forced, fake, or annoying, which we want to avoid. Indeed, live performances and moments of togetherness in the TOIVOLA “House of Hope” are valuable gestures to the community. For us, arriving there with something that’s too written doesn’t feel right. We want something alive. We want music, text, and dance to come together and for me, as a performer, that means asking “How can I function as a chameleon? How can different parts of me remain alive and accessible inside a space where I have a plan?” It’s related to the power we have as human beings to inhabit other modes of being and not get stuck inside of ourselves. For me, this level of awareness and attention is transformative.

Tilda: Lastly, in the performance, you’ll interrogate the idea of “talking heads” – referring to the expression, the camera technique, and the band. To me, the talking head, in our current media landscape, has a similar quality to the dramatic soliloquy, an element of privacy in a public exchange. You are stepping into this limbo already by both being a performer and a participant in the festival. How do you look at approaching this in-between state, between the performative and the private?

Kevin: The movement between public and private is definitely a part of what I’m doing, considering that behaviour creates gender. I learn from Judith Butler, who wrote that « gender proves to be performance, […] always a doing, though not a doing by a subject who might be said to pre-exist the deed » (Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990)). It’s complex in these terms, but I hold on to an awareness of private feelings, and I display them in public by conversing with my limits (e.g. for vulnerability) and navigating other’s responses. Concretely, last year, Guillaume recorded my voice while I was speaking into the microphone, and he played it back as an echo. That ongoing reproduction, putting thoughts on display and hearing them again and again, attracted me. I’m not interested in oversharing, but I do like moving through the world in ways where I’m as open and honest as I can be. While I’m not interested in policing an experience, I am invested in talking about feelings we share, challenging social spaces that we occupy, and putting what I learn from queer and feminist voices into practice. I owe a debt of gratitude to Minna Salami, Alok Vaid-Menon, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Judith Butler, Monique Wittig, adrienne maree brown, Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Astrida Neimanis and many, many more.

I’m aware of how complex and increasingly challenging the movement between public and private is, and how it informs everything I do as an artist. Indeed, I don’t want to be a head full of empty, pretentious ideas moving through the world, because in my opinion we can all choose to embody feminist principles. We can all choose to read queer theory and celebrate trans people and protect them when they’re in danger, like they are right now. That ability to choose and change then becomes a challenge when organising public experiences that come from personal desires: how do I produce something expansive, poetic, or open without it sliding towards a political rally? How can I propose a class where we’re all learning together without triggering power dynamics we may remember from school? That feels central to me when making performances.

« I chose blood and thunder as a title because human and ecological issues are intertwined with gender and other forms of discrimination. »

That movement between public and private is also why I chose blood and thunder as the title for the performance. Blood is something that we share, but it’s also something unique due to our genetics. Blood feels so tied to the way I write that I feel like I’m writing from a visceral, intimate need every day. At the same time, of course, performing in Helsinki with dance and text, I will make my body hot. I will make my blood boil. Thunder then contrasted this intimacy by referring to ominous news in the distance, danger outside the borders of my skin, while conjuring images of rain, lighting, booming sound and clouds. Inspired as I am by hydrofeminism, a feminist and environmental perspective that sees humans as interconnected with water, both in bodies and the environment, I chose blood and thunder as a title because human and ecological issues are intertwined with gender and other forms of discrimination. Thus, as a title, blood and thunder holds multiple things at once. Also, in research for the text, I learned that there is in fact an expression, “blood and thunder”, which refers to actions or stories that are overly dramatic, sensational, intense, exaggerated and expressive. When I saw that, I thought, “That’s perfect.”

To learn more and register for the performance and workshop taking place on 14 November at the TOIVOLA festival head to the event page on our website.

Photos by: Arnaud Beelen.